Vineyards

"My wines reflect their place, their terroir, so I let the vineyards shine, not my ability to change them."

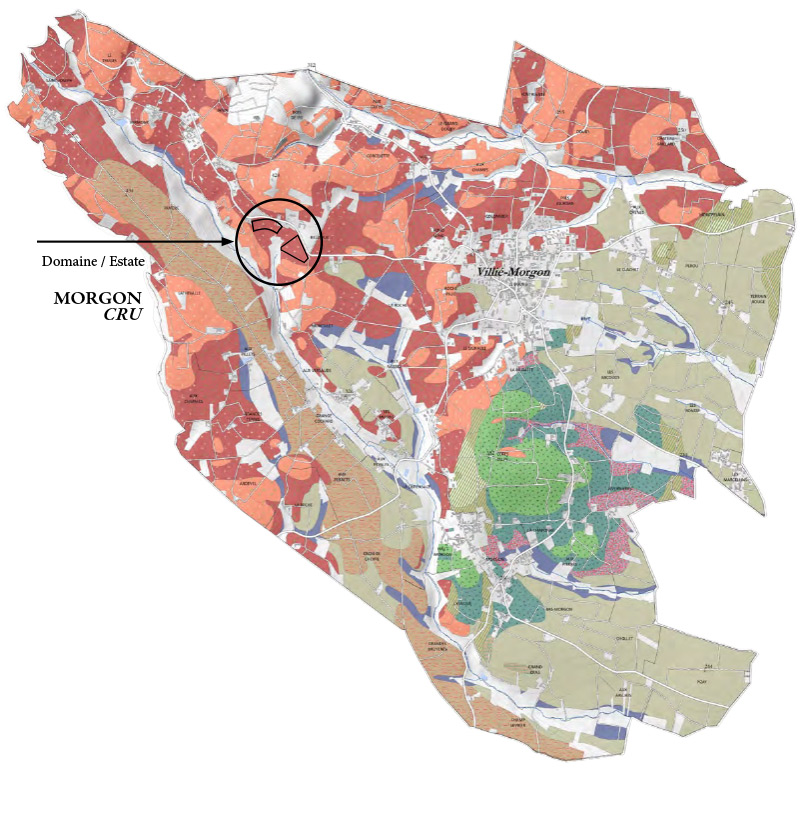

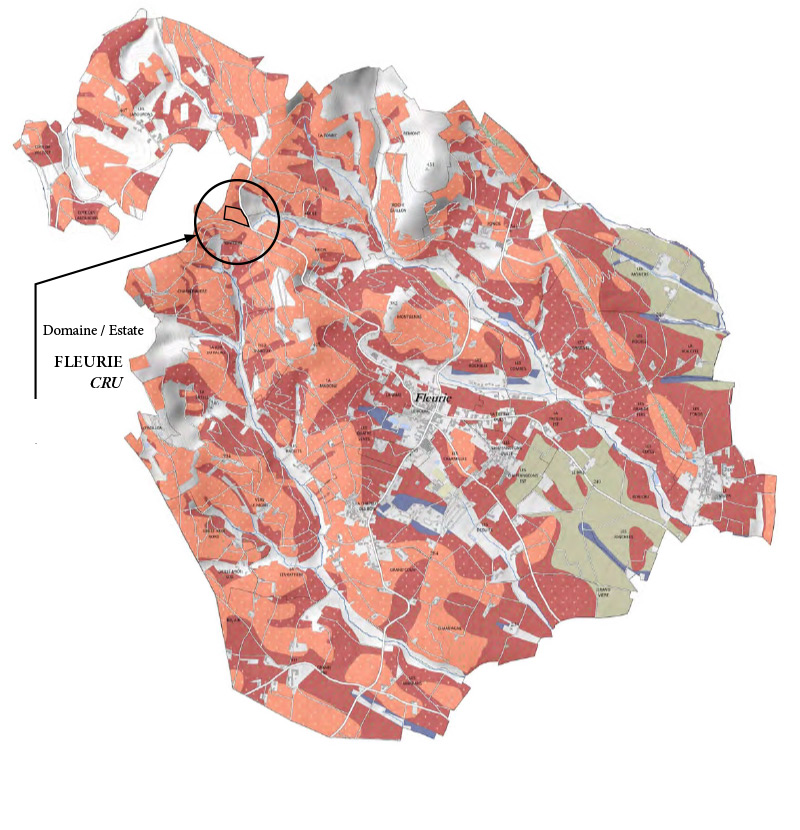

I make small-lot, vibrant natural wines from Morgon and Fleurie in central-eastern France - places where geology, altitude, climate, and culture create something truly rare. I chose these cooler, higher, steeper sites on purpose: they demand more work, but they make better wine.

My farming is unapologetically old-school - think 1920s farm manual. Certified organically farmed. Everything is done by hand, often with French plough horses. No petrochemicals, ever. Instead: diverse cover crops, organic compost, dry-farming, and welcoming the local ecosystem—bat boxes, insect hotels, all of it. It's a costly path, but it reveals the true character of these hills and treats the land, and our bodies, with respect.

At the end of the day, this is a plant-based, organic operation powered by people, horses, and hard work.

"Organically farmed, 70-year-old vines grown in steep, pink granite soils at over 460 meters (1,500') altitude is where extraordinary wine happens."

Jaw-Dropping History

Morgon and Fleurie have been growing wine for roughly twenty centuries—first under the Romans, then under Benedictine monks from the 7th to 10th centuries.

Their AOC "Cru" status was granted in 1936, the same year as Pauillac and Romanée-Conti. Prestige runs deep here.

These are tiny appellations: Morgon has just 2,745 acres, half of Napa's Oakville, and Fleurie is even smaller at 2,075 acres. Compared to places like the 140,000-acre West Sonoma Coast, they're specks on the map.

Both are almost entirely planted to Gamay, named after a small Burgundian hamlet. Gamay is a natural child of Pinot Noir and Gouais Blanc, and it delivers medium-bodied, velvety reds that punch far above their size.

Plough horses Pompom & Gingembre working the rows

Snowy winter sunrise in my Fleurie vineyard

Location, Altitude & Microclimate

Morgon and Fleurie are rugged, windy hills wedged between the Massif Central and the Alps in central-eastern France. On clear days we glimpse Mont Blanc to the east; Burgundy's Côte d'Or sits just a few kilometers north.

The best cru sites here share a few things: altitude, poor granite soils, old vines, and fractured terrain. These hills take everything nature throws at them - snow, sleet, hail, pounding rain, fierce wind, followed by long stretches of brilliant summer sun. Hard farming. Beautiful wine.

My Morgon "Bellevue" sits around 400 meters (1,310'). Fleurie "Fonfotin" climbs higher, to 460 meters (1,510'), on the far western edge of the appellation where winter snow is common. Meanwhile Pauillac, and even Romanée-Conti, sit comfortably near sea level.

Granite

In 2008, geologists launched a decade-long project to map every inch of the regions soils. They dug more than 15,000 six-foot pits, catalogued thousands of samples, and built a database no other wine region had ever attempted. The result is an unprecedented soil map—a mosaic winemakers once only dreamed of.

Out west in the Morgon and Fleurie appellations, the soils are ancient, eroded pink granite laced with quartz and mica, and colored by feldspar. Pure minerality. Rain drains fast through this rocky ground, pushing the vines to drive their roots deep. And unlike California, irrigation here is illegal—nature sets the rules.

My vineyards sit on:

- Morgon: deep, ancient pink granite

- Fleurie: shallow, eroded pink granite

My 70 year-old Gamay vines struggle in Morgon's pink granite soil

Hillside & high-density old vines deliver quality wines

In some of the cru appellations, the eastern vineyards are flat, fertile, and easy—loamy soils, tractors, big yields, modest wines, modest prices.

My vineyards sit at the opposite extreme. They're high on the western hills of Morgon and Fleurie, pitched at 20–40% slopes in hard granite. Everything is done by hand, vine by vine, at roughly 10,000 vines per hectare, about 2.5x Sonoma density. It's brutal, slow, and expensive.

French plough horses handle the steep rows with calm precision, threading tight spacing and rocky ground. Their "by-products" go straight back into the soil.

The vines themselves are old - planted in 1953, now over 70 years. Gnarled, head-pruned en gobelet, low to the ground. Painful to prune, painful to harvest, tiny yields. And still capable of producing great fruit for decades to come.

Naturally Organic Farming

My Morgon and Fleurie "Cru" vineyards are Certified Organic after a long, demanding three-year process. No toxic herbicides or fungicides. On steep slopes, that means more passes, more handwork, and more sweat.

Organic farming costs me about 25% more per hectare, and the yields are lower - no chemical shortcuts, no pumped-up vines. I spend more and harvest less.

Still, it's the only way to farm these hills honestly, and the only way to make wines that truly speak of their place.

Our "bug hotels" enhance ecological diversity in my organic vineyards

Selection Massale

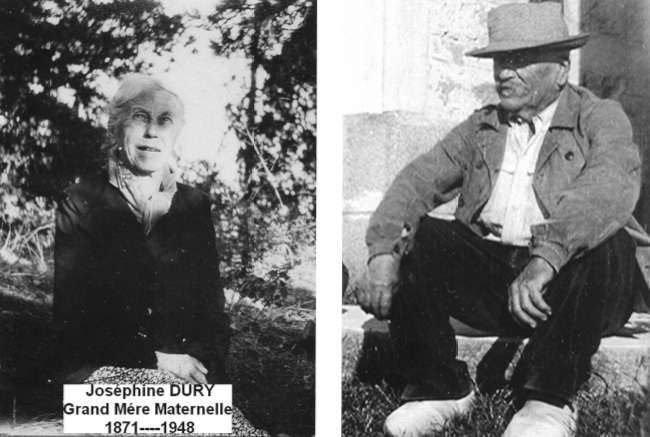

My Fleurie "Fonfotin" vineyard was first planted in the 1800s by Joseph and Josephine Dury Dargaud, then carefully tended by their descendants for generations. It's a rare, living piece of history.

The family later entrusted the vineyard to the region's top pépinière, masters of vine physiology and natural propagation. Their old-vine sélection massale cuttings were coveted by the best growers in Beaujolais.

Sélection massale is slow, hands-on, and deeply unfashionable, nothing like modern cloning. Over multiple seasons, buds are chosen from the very best vines, propagated naturally, and replanted to preserve real genetic diversity. Think heirloom seeds, not industrial clones.

Those celebrated vine cuttings material were planted on my steep Fonfotin site over 70 years ago, behind original granite stone walls. The vines are uneven, yields are tiny, and the wines are anything but ordinary.

![]()

This vineyard is pure terroir—certified organic, genetically diverse, and extremely rare. There's very little of this Fleurie. Please savor it.

What does "Cru" mean in Morgon and Fleurie?

In France, cru means "growth", a tightly defined place officially recognized by the INAO for exceptional grapes and wines. Beaujolais has just ten crus, more akin to Champagne's vineyard system than Bordeaux's.

A cru isn't just geography. It comes with hard limits: a maximum yield of 48 hectoliters per hectare (about 3.1 tons per acre - roughly half California's average). In reality, nature usually cuts that down. In 2022, my Morgon yielded just 25 hl/ha. In 2024, my Fleurie yielded nothing. Ouch.

Cru rules also lock in the essentials: Gamay only, a minimum of 10.5% alcohol, grapes fermented and bottled locally, and a mandatory blind tasting before release.

In short, a cru is terroir with teeth - legally defined, strictly regulated, and designed to ensure the wines reflect the very best of a very small place.

"Lieu-Dit"

My Morgon and Fleurie vineyards also carry prestigious lieu-dit names: Morgon "Bellevue" and Fleurie "Fonfotin." The idea dates back to 640 in Gevrey-Chambertin—a lieu-dit marks a tiny parcel recognized for its unique soil, slope, and microclimate. Burgundy calls these climats, but the meaning is the same: a small patch of earth with its own voice.

"Bellevue" and "Fonfotin" are quietly famous among Paris's savviest sommeliers, yet still rare in North America.